Dr. Trusit Dave, PhD, BSc(Hons), MCOptom, FAAO. & Dr. Sunil Mamtora, MBBS.

Introduction

There are several definitions of informed consent but broadly speaking informed consent is a process for getting permission before conducting a healthcare intervention on a person, or for disclosing personal information.

It has been proposed that for consent to be valid there are five conditions that need to be met1:

(a) Information disclosure: provision of adequate information about the intervention

(b) Competence: capacity of the patient to understand that information

(c) Voluntariness: decision making in the absence of coercion or deception

(d) Comprehension: patient understanding of information provided

(e) Consent: agreement to the proposed treatment or procedure

Research assessing the completeness of informed consent has shown that only 9% of patient consenting is performed fully2. Furthermore, the most common omission is evaluating patient comprehension (only 1.5% of 1057 consultations)2.

Of 1057 Physician consultations, only 9% were completed with full informed consent2

Evaluating patient comprehension was only performed in 1.5%-12% of informed consent consultations2,3

More specifically to Ophthalmology, Pesudovos et al4 evaluated patient recall following informed consent consultations with and without written documentation in a randomized prospective study of 50 subjects listed for planned cataract surgery. Their study demonstrated that written information did not increase patient recall of complications or success rates of cataract surgery. Although subjects were happy with the information they had been given, they did not remember enough from the informed consent process to satisfy legal requirements.

Based on the research cited above, it would seem logical that the consent process could be improved by delivering information using alternative methods. However, the consent process would also need to include a way to document what the patient has understood by way of a short questionnaire.

Improving Patient Understanding

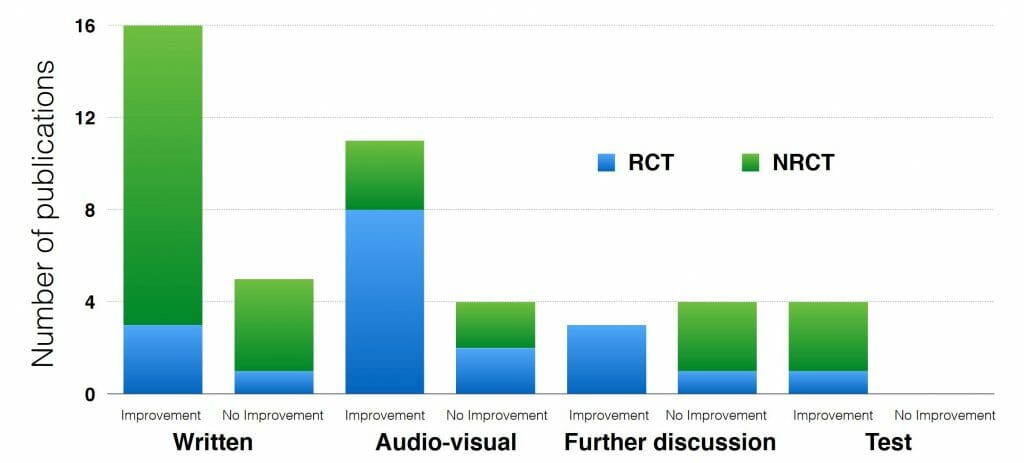

There are many publications that have evaluated patient understanding through varied approaches of information delivery. A systematic review by Schenker et al5, has shown that a variety of alternative approaches lead to improved comprehension. Specifically, audio-visual information was shown to have the largest improvement for patient comprehension in their systematic review of randomized controlled trial studies. One study in particular6, showed six times increase in patient comprehension.

Randomized control trials have shown that audio-visual information has an improvement of patient understanding according to a systematic analysis of publications5.

Improving Efficiency

The use of multi-media patient education tools offer a number of advantages over the conventional approach to verbal counseling. Firstly, the information presented with sequential video playlists is always consistent, verbal communication may be variable. One should note that face-to-face consultation is not to be replaced with video playlists. The consent process should always offer the patient the opportunity to ask questions with a member of the clinical team (ideally the operating surgeon).

Secondly, the amount of time spent by clinical staff may be reduced. A recent study showed significantly reduced consultation times when multi-media presentations are used during informed consent for laser refractive surgery7.

Cost of Litigation

Patients are all too aware of legal firms that offer ‘no-win, no-fee’ services. The cost of litigation within ophthalmology is more frequent in cataract and corneal procedures – one such study cites approximately 50% of closed claims being attributed to these areas8. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, cataract was the biggest cause for medico-legal claims – accounting for 34% of all claims between 1995 and 20099.

Within the United States the cost of medico-legal claims against ophthalmologists over a 10-year period between 2006 and 2015 was found to be in excess of $160 million dollars8. Rashmi et al state that cost to the National Health Service (which does not include private Ophthalmologists) was in excess of $50 million dollars over a 15-year period.

Considering the increasing trend of procedures such as refractive lens exchange and implantable collamer lenses as well as the innovations in premium intraocular multifocal lenses, patient understanding of potential visual and surgical complications is essential.

A New Electronic Consent Tool

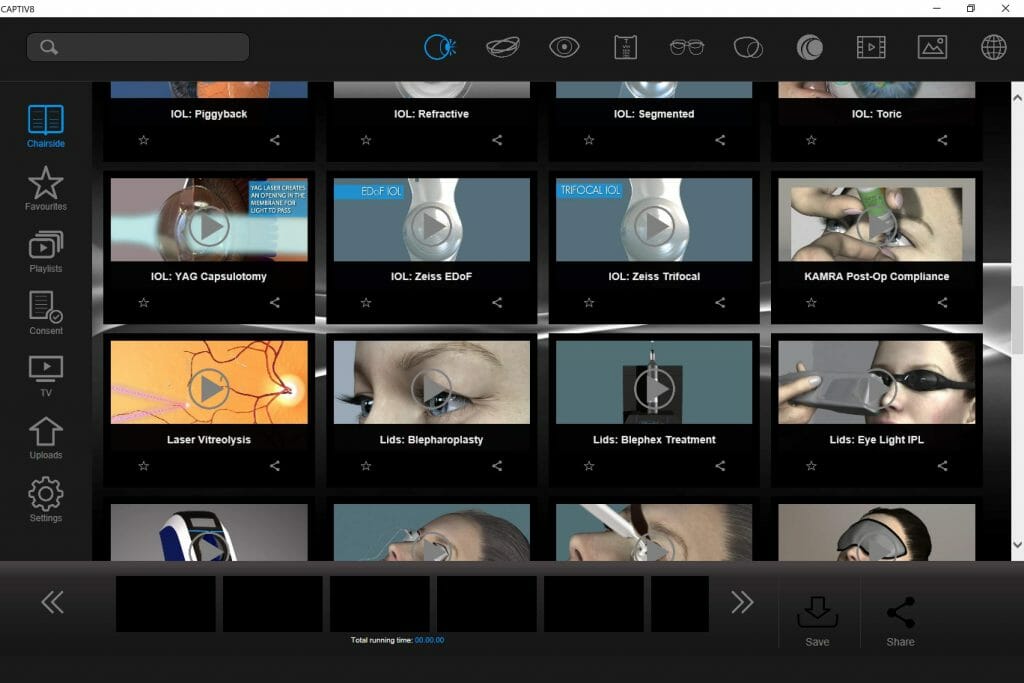

Recently, Optimed (www.optimed.co.uk) launched a new consent tool as part of their CAPTIV8 product in order to save time and improve the consent process. The company produces an extensive library of 3D medical animations (in several languages) that cover a wide range of eye conditions and surgical procedures in Ophthalmology within a patient communication software platform (CAPTIV8).

Shows the CAPTIV8 software interface. A comprehensive library of high quality 3D animations covering ophthalmological conditions and surgical procedures/treatments.

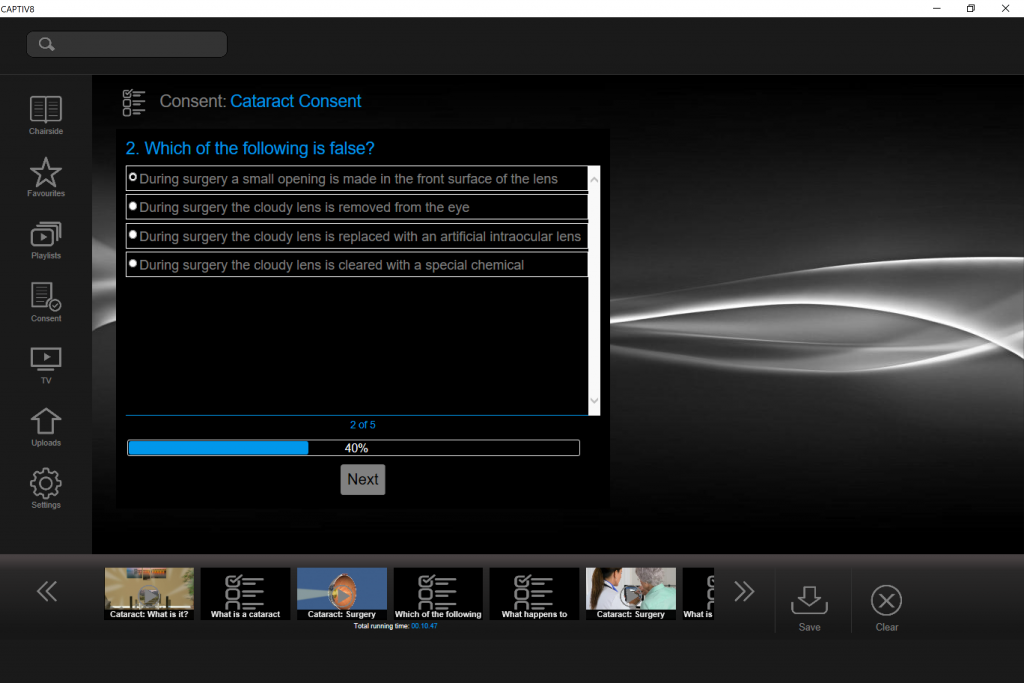

The consent tool allows Ophthalmologists to create customized playlists of animations and also upload their own videos in order educate patients as part of the consent process. The tool also allows surgeons to add questions in order to assess patient understanding in-between animations within the playlist. Incorrect patient responses are highlighted, and the patient is directed to the correct response with an acknowledgement from the patient that they have understood the correct answer.

Video presentations have shown to significantly reduce clinician time7

The CAPTIV8 Consent add-on allows users to assess patient understanding in the form of questionnaires that are created by users for specific surgical procedures. The questions are asked at user-defined intervals between playlists of animations.

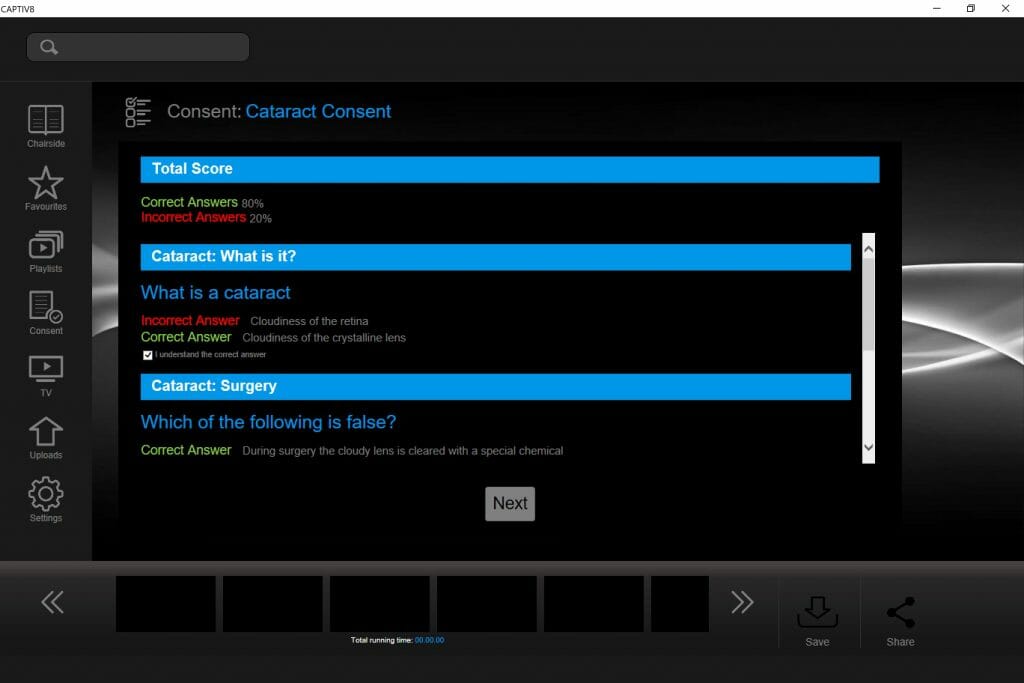

Once the playlist is completed, the patient is presented with their score and corrections. Each consent playlist is also associated with a specific legal consent document (which can be uploaded by the clinician into the CAPTIV8 platform). Hence, once the patient has evaluated their score, they can read the consent document and then electronically sign the consent document (using a tablet such as an iPad). CAPTIV8 Consent then merges the signed consent document and patient questionnaire into one pdf document which is automatically sent either to a specific email, EMR platform or even to the patient.

Once the questionnaire is completed the results are presented in a summary. The patient is then shown the practice’s informed document for that procedure which the patient can electronically sign on an iPad.

Summary

Most informed consent is not complete according the requirements of the widely accepted consent definition criteria. The most common omission during the consent process is the assessment of patient understanding. Multimedia presentations have been shown to be effective in enhancing patient recall compared to conventional verbal communication.

The new CAPTIV8 Consent platform offers high-quality 3D animations to improve education and allows the clinician to add multiple choice questions in order to evaluate and record the degree of patient understanding. The CAPTIV8 Consent tool also streamlines the consent process by allowing the clinician to add specific consent documents so that electronic signatures can be captured and merged to form a single pdf containing signed consent and patient assessment data that can easily be attached to patient electronic medical records.

References

- Beauchamp TL, Faden RR. In: Encyclopaedia of Bioethics. Reich WT, editor. Vol. 14. New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan; 1995. Informed consent: II. Meaning and elements of informed consent; pp. 1240–1245.

- Braddock III CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed Decision Making in Outpatient Practice: Time to Get Back to Basics. 1999;282(24):2313–2320. doi:10.1001/jama.282.24.2313.

- Braddock C 3rd, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, Bereknyei S, Frankel RM, Levinson W. “Surgery is certainly one good option”: quality and time-efficiency of informed decision-making in surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(9):1830–1838. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00840.

- Pesudovs, K, Luscombe, CK, Coster, DJ. Recall from informed consent counselling for cataract surgery. J Law Med. 2006;13(4):496–504.

- Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Sudore R, Schillinger D. Interventions to Improve Patient Comprehension in Informed Consent for Medical and Surgical Procedures: A Systematic Review. Med DecisMaking. 2011;31:151–173.

- Done, ML, Lee, A. The use of a video to convey preanesthetic information to patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 1998;87(3):531–6.

- Baenninger P, Faes L, Kaufmann C, Reichmuth V, Bachmann L, Thiel M. Efficiency of video-presented information about excimer laser treatment on ametropic patients’ knowledge and satisfaction with the informed consent process. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018 Dec;44(12):1426-1430. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.07.052. Epub 2018 Sep 28.

- Thompson A, Parikh D, Lad E. Review of Ophthalmology Medical Professional Liability Claims in the United States from 2006 through 2015. Volume 125, Issue 5, May 2018, Pages 631-641.

- Mathew R, Ferguson V, Hingorani M. Clinical Negligence in Ophthalmology: Fifteen Years of National Health Service Litigation Authority Data. Volume 120, Issue 4, April 2013, Pages 859-864.